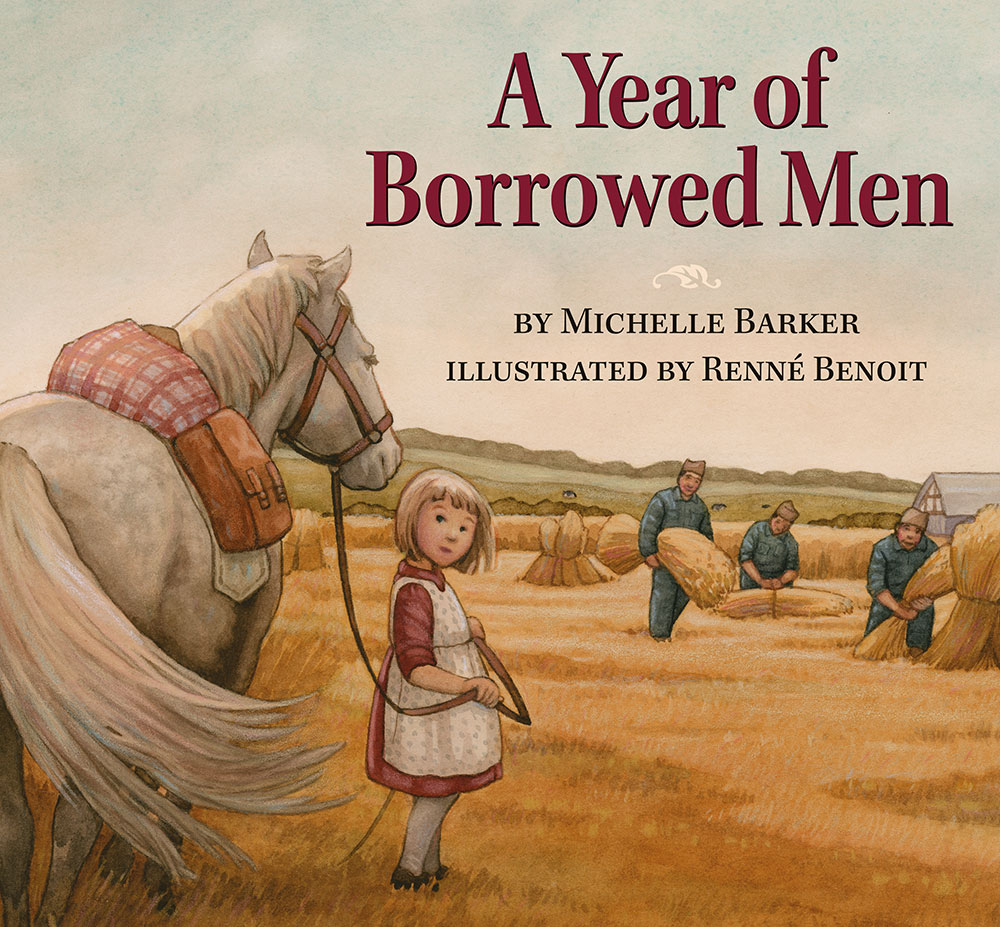

As I’ve no doubt mentioned before, I love historical fiction based on a family story. And Michelle Barker’s A Year of Borrowed Men (Pajama Press), with luminous art by Renné Benoit, had me from the first page. Why? The voice. Told as though we’re hearing it straight from Gerda, Michelle’s mother, you’ll feel, as you read, like you’re sitting beside her, hearing this tale of light in the midst of what, for her family and millions of others, was a very dark time.

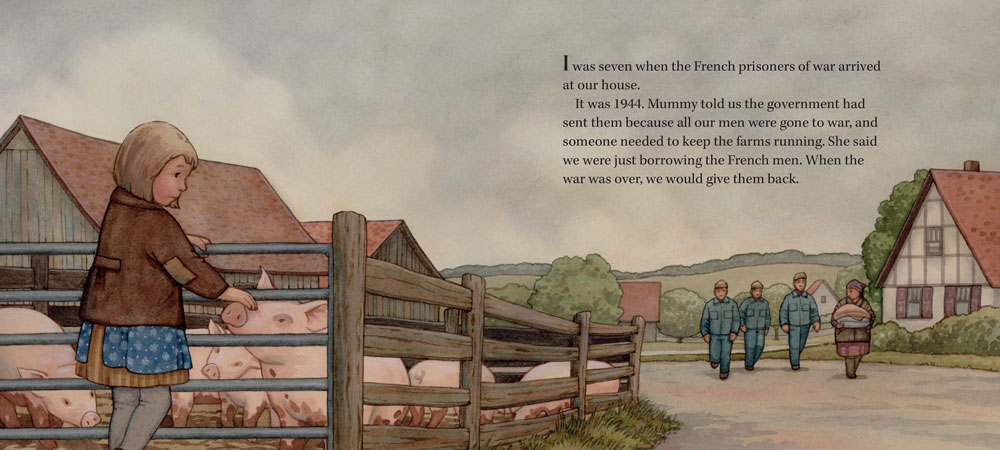

From the title page: “When World War II ‘borrows’ most of the men in Germany, six-year-old Gerda’s family is allowed to borrow three French prisoners of war to help run their farm. They are supposed to treat the men as enemies, but the family finds clever ways to show kindness and friendship.”

School Library Journal says, “…this precious gem evokes compassion in a way that is sure to resonate with young audiences.”

Kirkus Reviews calls it “A tender memoir of human decency during wartime…”

All artwork ©Renné Benoit and courtesy of Pajama Press.

Gerda’s father and brother are serving in the war, so their family farm is allowed the temporary help of three French prisoners. They are, the family is warned, to be treated as enemies. But that is next to impossible when the men turn out to be “gentle Gabriel, prickly Fermaine, and cheerful Albert, who loved games.” Real people, no longer the nameless, faceless Enemy.

The men are housed in the family’s “pig kitchen,” but the family quickly takes to them, eventually inviting them into the house to share a meal. A neighbor turns them in for that, and the police show up to threaten Mum. But as Christmas approaches, Gerda comes up with a unique and sweet way to help the men celebrate the season. There’s an especially touching situation with Gerda’s new and beloved doll that bonds her to the Frenchmen.

Michelle has written a author’s note at story’s end and included family photos so readers can see the real Gerda. A gentle tale with a lot of heart, what this touchingly-real story ultimately offers up is hope. This is one you should see.

Michelle agreed to answer a few questions for us.

JE: Do you recall when you first heard this story of your mother’s childhood?

MB: I don’t. My mother tended to tell the stories of her childhood in bits and pieces. I came to think of them as treasures she kept stored on a high shelf that only came down on special occasions. They must have been difficult for her to tell. But I remembered them. During my MFA degree in creative writing, I took a course on writing for children and we did some sessions on historical fiction. One of our assignments was to write a historical story and the first thing that popped into my head was the image of the Christmas tree with pictures cut from catalogues. That was where this book began.

JE: Was it difficult deciding how you’d approach the story (opening scene, point of view, tense, etc)?

MB: I knew this was my mother’s story and I decided early on to tell it from her point of view. More difficult was the decision of whether to have her looking back on this period in her life, or being “in” it. I opted for immediacy. Deciding on the arc of the story took some time. In the first draft the focal point was Christmas (the original title was The Catalogue Christmas Tree). But my biggest challenge was with the ending, which was also what changed the story’s arc. I needed to find a way to focus on something positive. I realized the borrowed men were key, that there is always common ground between people if you look for it.

JE: Did you make any changes to the original story?

MB: One thing I changed was who rescued my mother’s doll. In reality it was her sister, but I wanted to use that scene to cement the commonality between my mom and the borrowed men, so I took some creative license.

I was also mindful of being gentle at the end. The true story doesn’t end well. My mother lost both her brother and father in the war, and when the Russians arrived she and her family had to abandon everything and flee. It’s heavy material, and I’m writing about it now in an adult novel. For children I had to soften the ending and keep the focus on friendship.

JE: Could you talk about why you think it’s important that today’s children learn how historical events affected real families?

MB: When you only read about history in textbooks, you tend to forget that real people are involved, with needs, dreams and desires like us. Particularly with respect to World War 2, it would have been difficult to grow up German and be saddled with (possibly) unfair assumptions about your character. Learning about history in a more personal way allows us to put ourselves in another’s shoes, which is the beginning of compassion.

To learn more about Michelle Barker, visit her website.

Thanks, Michelle, for giving us a peek at your beautiful story.

Readers, for more poignant stories from the WW II home front, take a look at these:

One Thousand Tracings, by Lita Judge; Boxes for Katje, by Candace Fleming; Pennies in a Jar, by Dori Chaconas, and I Will Come Back for You, by Marisabina Russo

Jill Esbaum

This looks amazing! I am so impressed!

Thank you!

So happy you shared your story, Michelle! I can’t wait to read it.

Thank you so much. I hope you enjoy it 🙂

I will certainly share this with my friend Gerda W. who is coming to town this weekend. She was born in Lithuania in 1936 and has many similar memories.

Thank you! evie

Wonderful. I’d love to hear what she thinks about it.

This looks powerful. Beautiful too. Thanks, Jill, and congratulations, Michelle. (I like your title change, also!)

Thanks. And yes, I think the title is better now too.

Looks like a lovely book! Thanks, Jill!

Thank you!

The simple art perfectly complements the sweet story. Great work!

I was very lucky to have Renne Benoit as the illustrator. I love the artwork she did.

What a wonderful way to weave family stories and make history more personal.

Thanks for this great recommendation, Jill!

I will buy this tomorrow. It looks wonderful and I love knowing the story behind it. I wish that I had been able to take children’s writing at UBC-my one regret.

Susan Young (from fiction)