If you’re a picture book writer — aspiring or published — you’ve likely heard someone say: “Don’t write your story in rhyme. Editors say they don’t want that.”

Then, arguments often ensue, with some people talking about how rhyme helps beginning readers learn to process language, and other people talking about how Dr. Seuss rhymed and his books are still in print, and others talking about how they just can’t think of their story in any way but rhyme, and whatever will they do?

A quick look at recent picture book releases shows editors are acquiring rhyming picture books and always have been. Editors I’ve talked to say of course they’ll consider rhyme, but they see so much bad rhyme that it worries them a bit when they hear a story is in rhyme. (And, as someone who often critiques manuscripts for conferences or other projects, I can relate. I’ve seen rhyming stories that are so well-intentioned but poorly executed that it makes my head hurt.)

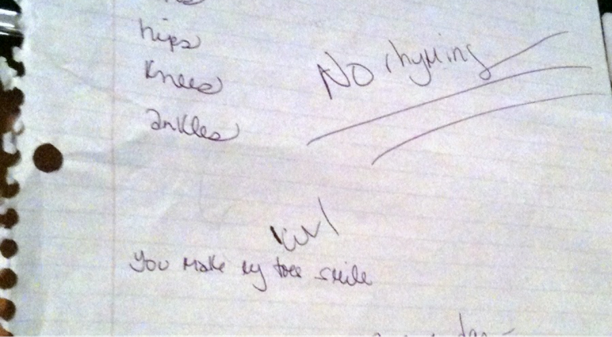

The thing is. Writing in rhyme properly is harder than writing in prose. The initial drafting process is harder. Revising is harder. If your book sells and someone wants to buy foreign rights, translating it is harder. (What rhymes in English won’t rhyme in Dutch or Mandarin Chinese.) Even though I’ve successfully written rhyme and likely will again, I often write myself notes on story ideas like this one that say “No Rhyming.”

So what’s a rhymer to do? How can you make sure your rhyming story is well done? I’m so glad you asked.

Here are my steps for writing a story in rhyme that works. And, I’m using a beautiful new rhyming picture book to illustrate my points. Meet FEDERICO AND THE WOLF by Rebecca Gomez with illustrations by Elisa Chavarri. It came out this year from Clarion Books.

STEP ONE: ARE YOU TELLING A COMPLETE STORY?

When you write in rhyme your story has to do everything a prose picture book does. Sometimes, rhymers get so caught up in their rhyme, they forget this. So look at your story. Does it have a main character? Is there an obstacle to overcome? How does that happen? Does the character grow and change? Is there a satisfying resolution? Is the story well paced? Does the reader feel something after they close the cover?

FEDERICO is a retelling of Little Red Riding Hood — with a lot of twists. Federico — a boy — is Little Red. He has a red hoodie instead of a cape. And he’s taking groceries to his abuelo on his bicycle. There’s the woods and a wolf, and a confrontation, but Federico outwits the beast using his wits and the contents of his grocery basket in an unexpected way.

If Rebecca Gomez had written this story in prose, it would have held up well and been a thoroughly satisfying read. A good test for your in-progress story is to write it in prose just to make sure there’s enough heft to your tale.

STEP TWO: HOW’S YOUR METER?

Some beginning rhymers think that if the words at the end of their sentences rhyme, that’s all they need. Not true. Rhyming picture books use a variety of rhythms and patterns called meter that help the story flow and make it fun to read out loud.

You may have heard that Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter. That’s one of many arrangements of stressed and unstressed syllables rhymers can choose. Here’s what the beginning of Rebecca’s story looks like with the stressed beats capitalized and unstressed ones lower-cased. As you can see, she’s alternating stressed and unstressed beats.

ONCE uPON a MODern TIME

a BOY named FEDerIco

LEFT to BUY inGREDiENTS

to MAKE the PERfect PIco.

Along with noticing the pattern of stresses, note that each of these lines has exactly seven syllables. What pattern is your story following? Are you consistent? If you’re not, is there a strong reason for why you’re switching around?

I’ve sold four rhyming picture books — WHEREVER YOU GO, SHARING THE BREAD, REMARKABLY YOU and the upcoming WHEN I’M WITH YOU — but I wouldn’t say I’m an expert at meter. Do you know who is? Dori Chaconas. Her website has a whole section on meter and how to use it. Go there, and get all the details.

If you’ve got your meter right, any reader can pick up your book and read it properly. Have you ever read a rhyming book where you struggled to get in the flow or it took you a few pages to figure out how to read it?

It’s likely the meter was off.

STEP THREE: WHAT ABOUT YOUR RHYME?

Rhyming books do need to rhyme. And just like there are many options for meter, there are many option for rhyme schemes. Here’s what Rebecca used in FEDERICO:

“Cuidado!” called his mama

as he pedaled toward the shops

“Mind Abuelo’s grocery list,

and don’t make other stops.”

As you see, every other line rhymes. Again, it’s important to choose a rhyme pattern and use it consistently in your book — unless you consciously choose to change it up with, say, a refrain that uses a different pattern.

Also, look at your rhymes. Are they true rhymes? As in, do the words rhyme perfectly, like “shops” and “stops”? Or, are they near rhymes? As in, the words almost rhyme, but not quite — like in the country song “If It’s Meant to Be” by Bebe Rexha and Florida Georgia Line It starts:

Baby, lay on back and relax.

Kick your pretty feet up on my dash.

No need to go nowhere fast.

Let’s enjoy right here where we’re at.

“Relax,” “dash,” “fast” and “at” kind-of, sort-of rhyme. They all have that common “a” sound. But they don’t truly rhyme. Songs can get away with this. Picture books mostly can’t. (You may want to argue with me, but it’s true.)

STEP FOUR: WOULD YOU SAY IT THAT WAY?

All right. You’ve reviewed your story. It’s got a compelling plot. Spot-on meter. Pitch-perfect rhyme. Now you’ve got to ask: “But, if I were having a conversation with someone, would I say it the way I wrote it here?”

Now, I’m guessing you wouldn’t have a conversation in rhyme. But, if you did, would it sound reasonable? When Federico confronts the wolf, who is pretending to be his grandfather, Rebecca writes:

By now, the wolf was drooling.

“All this chatter’s getting old.

I’m hungry, bub. I need some grub

before I pass out cold.”

This sounds like an actual conversation someone would have. But, sometimes, rhymers — in an effort to get that perfect rhyme — twist sentences around in a way that no one would say like:

The hungry wolf stared at the wall.

“Whatever shall I do?

If I cannot find some food,

then to the floor I’ll fall.”

To be clear, this is NOT from the book. It’s something I quickly wrote as a (very) bad example. If I were hungry and talking to you, I wouldn’t say “and to the floor I’ll fall.” I’d say “I’ll fall to the floor.” Or, “I’ll fall down.” Or, just, “I’ll fall.” This stanza only uses “then to the floor I’ll fall,” because it needs something to rhyme with wall.” You want your rhyme to sound as natural and effortless as a good conversation.

All these steps are what make rhyming well so hard. If you want to master rhyme, the best thing you can do is read a lot of top-notch rhyme — like this new book from Rebecca Gomez. (And, did you notice? Not only are her story, meter and rhyme perfect, she does this using a mix of English and Spanish words. Major bonus points for that.)

There are a few authors whom I consider reigning rhyming royalty, and I’d recommend reading every rhyming book they’ve written:

- Linda Ashman

- Dori Chaconas

- Jill Esbaum

- Corey Rosen Schwartz

- Lisa Wheeler

- Karma Wilson

So, go forth! Read lots of wonderful rhyme. Study how it’s set up. Then, revise your own accordingly. Set it aside. Work on it some more. And, when you and your critique partners think it’s ready, submit it with a clear conscience.

What a fantastic and helpful post!

Thank you for showing the way rhyme should and should not be used. The link to Dori’s site is gold!

Wow! This is a great post -packed with helpful information -thank you!

This is a super helpful post. Thanks!

This was a great post! Thanks, Pat. I will most definitely read this book.

Excellent post! Thanks, Pat!

Thank you Pat. I always need a refresher on rhyming stories every so often.

As someone who must critique a lot of bad rhyme and sorry meter, thank you!

Spot on! Thank you for this great post!

Thanks, Pat, for sharing the steps to writing in rhyme. Rebecca’s book is a wonderful mentor text, as are the other authors’ books you listed, for excellent rhyming examples to study!

Thank you, Pat, for sharing these great suggestions and examples. I know when not to step into these waters, but I sure admire those who do it so perfectly.

Very helpful post. I really appreciate your good examples.

Yes! I would add Julia Donaldson and Sue Fliess to the rhyming master list. It sounds like I need to get this book as a mentor text. Thanks for the rec!

Thanks, Pat. What a wonderful post about rhyme.

Your posts are so fun to read and informative, Pat. Thanks for sharing your knowledge. There are a few authors here I’m excited to check out AND this post reminded me to make a library request for Federico and the Wolf AND Everywhere You Go. Win, win, win.

Congratulations to Rebecca on her new book.

Great post, Pat! Wonderful tips on rhyme. I’m looking forward to reading Frederico and the Wolf!!

I send rhymers to Dori’s website all. the. time. LOVE this post!

(Also, thank you!)

This is great, Pat!! Thank you so much! Great authors with great examples.

Cute story! And excellent examples of good rhyme! Thank you!

Great tips!

Oooh, another PB to add to my TBR list! Thanks, Pat! 🙂

What an excellent, concise lesson on writing in rhyme! Thanks, Pat! The other thing I love about Gomez’ use of English and Spanish, is that it helps the reader know how to pronounce what might be an unfamiliar word!

Great post, Pat. As always, you’ve packed in a ton of useful information.